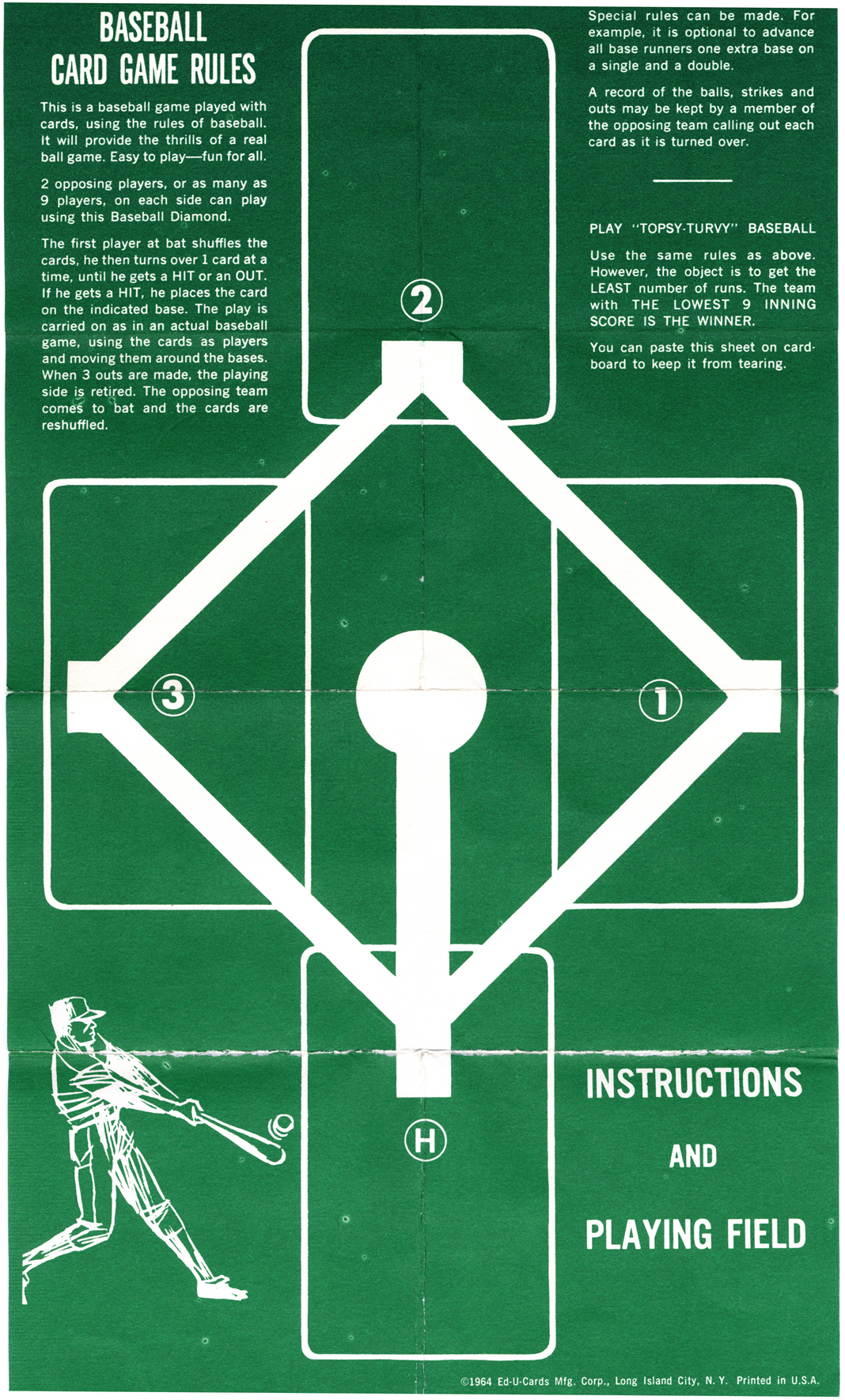

Blaseball, the little baseball idle game that could. Watching the community around this game develop and grow was one of the things that brought me the most joy this year. Go Garages!

My favourite Blaseball game of the year was on Season 7, Day 10: a newly-revived Jaylen Hotdogfingers leads my beloved Seattle Garages to a 6-5 12-inning win over the Canada Moist Talkers and their first-ballot Hall of Fame pitcher PolkaDot Patterson. LANG GANG!

Jon Bois had another banner year: the co-founding of the Secret Base imprint, joining Kofie Yeobah in the continuing madness that is Fumble Dimension, a sequel to 17776 called 20020, and of course, a towering directorial achievement in The History of the Seattle Mariners, which he co-wrote with Alex Rubenstein.

Rewatching John Berger's seminal miniseries Ways of Seeing.

The unkillable cultural behemoth known as Jank City, the dollar-store pack Magic: The Gathering draft I hold every six weeks or so. We haven't been to the LGS in a minute, but the event continues in cyberspace.

Finally got a big-ass TV. So many pixels! Naturally, I broke it in with Heat on Blu-ray.

Introducing three local poets to dril's Betsy Ross Museum tweet over post-reading poutines.

Writing 29 capsule reviews of 29 new-to-me albums as part of Gary Suarez's Music Writer Exercise (#MWE). Here's a thread of them.

Parasite winning four Oscars, including Best Picture.

A 42-year-old Zamboni driver named David Ayres coming into a Canes/Leafs game as an emergency goalie and getting the W. He's even got a Hockey Reference page now!

Celebrating 11 years with my lovely partner Steph.

Starview HCT-5808, a weird sci-fi relic from the Laserdisc era that I stumbled upon on YouTube. It's just... stills set to a jazz fusion score. It rules.

All Fantasy Everything, still the podcast I look forward to hearing the most on a weekly basis. Their Sneakers draft is a perfect episode because I don't know shit about sneakers, but these dudes are so funny that it doesn't matter.

The ongoing adventures of my Mastodon instance, laserdisc.party.

Related: #VerseThursday. (Also here.)

Four words: Animal Crossing: New Horizons. A balm in a year where we couldn't get together IRL.

Speaking of New Horizons: Nicky Flowers's mashup of the game's 12pm theme and Nelly's "Country Grammar (Hot Shit)."

Fleet Foxes' Shore, my absolute favourite record of the year. It's a brilliant synthesis of the cinematic folk and jazzbo accents present on both Helplessness Blues and Crack-Up, and the result is my favourite record of theirs since their self-titled one.

Every day I record an episode of Middlebrow Madness with my pal Isabelle is a great day. The show has become weirder and more digressive in 2020, and I think it's better for it.

Speaking of Isabelle, I loved this piece she wrote about M. Night Shyamalan's Signs, published on the still-chugging Dim the House Lights.

I watched some bangers for the first time thanks to the podcast: La haine, Wild Strawberries, Das Boot, The Wages of Fear, Sunrise, Amadeus, Before Sunset, Diabolique.

I didn't see a ton of movies from 2020 last year, but I did see a bunch of great movies for the first time even outside my homework for the show: Bringing Out the Dead, Bait, Ocean's Eleven, the Lord of the Rings trilogy (theatrical cuts only), Local Legends, The Big Easy, Tombstone, Yes, Madam, Righting Wrongs, Glass Chin, Gemini.

Incidentally, I bought my copy of Local Legends from Toronto's Gold Ninja Video, the Criterion Collection of regional whatsits, forgotten kung fu movies, and public domain junk.

Justin Decloux, the head honcho of Gold Ninja Video, and fellow Torontonian Will Sloan have a wonderful podcast called The Important Cinema Club, where they talk about everything from classic Hollywood films to Hong Kong Category III joints to vintage porn.

Poetry night on Wednesdays. I didn't write as much this year, but I think the output was better overall.

The good people over at Cactus Press were kind enough to publish three of my poems ("Oxblood," "Brain Sieve," and "Dream #9") in their online magazine, Lantern.

Two of my closest poet friends put out chapbooks on Cactus last year: James Dunnigan with Wine and Fire, and Frances Pope with The Brazen Forecast.

Game night every Friday, without fail. Lots of Codenames, lots of Jackbox. Like Animal Crossing, Jackbox Party Pack 7 could not have come out at a more opportune time.

We did trivia a couple of times for game night. I miss pub trivia. I miss bar nachos.

This is not really the way I wanted it to happen, but I did solidify my friendship with the game night regulars. You know who you are.

I made a pepperoni pizza from scratch and it tasted amazing.

I became an Instant Pot true believer. I made so many soups and stews. It's become my favourite tool for making mashed potatoes. I made eggplant parmesan once, I mean, fuck.

Saturday night Commander. So many degenerate brews.

You know what Magic format was super fun? Jumpstart.

Super Mega Baseball 3 on Switch. Easy to pick up, ridiculously customizable, very fun.

The Omnibus podcast, hosted by indie-rock luminary John Roderick and Jeopardy! legend Ken Jennings.

Revisiting the catalog of the late, great John Prine. I love this set he cut for Sessions at West 54th in 2000.

"City Pop Films."

The 8-bit-styled statistical esoterica of Foolish Baseball.

Writing secret songs.

Seeing The Irishman with friends in the dead of winter at a run-down theatre in a failing mall after having filled our bellies with Korean food.

Making all kinds of playlists on Spotify. There are the Quarantunes lists (a series hour-long songs-of-the-month digest; here's the ninth and final one I put together), some 10-track artist primers (including Rush [RIP Neal Peart], Deerhoof, and Tom Waits), and my favourite, a collaborative playlist with some friends that is now 600+ songs strong.

Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, who has a very real claim to being my favourite film writer, wrote a eulogy for Chicago cinephile institution Odd Obsession.

New favourite writing tool: paint markers.

The Merlin Mann Podcast Universe (Back to Work, Do By Friday, Reconcilable Differences, Roderick on the Line, and a returning You Look Nice Today called California King) continues to deliver.

Not only super-niche, but also in French: the oral history of Roller Hockey International's Montreal Roadrunners.

The fried chicken at Poulet Bronzé, the site of my last social outing before the world ground to a halt.

Hot on the heels of their wonderful 2019 album Oncle Jazz and a few great singles this year, Men I Trust may very well be my new favourite Montreal band.

Another band I fell in love with this year was Chicago's Beach Bunny. Honeymoon is one of my favourite records from this year. Very feels, very 90s.

Speaking of music from Illinois: 2020 featured the return of Champaign's mighty Hum. Inlet was their first album in over two decades, and it was worth every second of the wait. An hour of crunchy, shoegaze-y space rock.

Stasis Sounds for Long-Distance Space Travel by 36 and Zakè, a 96-minute sci-fi drone/ambient concept album about the loneliness and majesty of outer space.

The melancholic bedroom pop of Su Lee.

My mom got our cats a cat tree for Christmas. It's exactly as adorable as it sounds.

Graeme Laird, aka Doc Destructo, late of the great WCW podcast The Greatest Podcast in the History of Our Sport, only put out two YouTube videos this year, but they're both incredibly written and fucking hilarious. One is about the notorious Charles Bronson vehicle Death Wish 3, and the other is about the gloriously cheap Italian Star Wars knockoff Starcrash.

I started running and minding what I ate and I lost nearly 25 pounds.

For Interview magazine, Marilyn Manson interviews Nicolas Cage.

Dan Deacon's album Mystic Familiar. This manages to be very introspective without sacrificing the sugar-rush highs of his older work.

I'd like to plug the work of one Nathan Smith, a writer from Knoxville currently based in New York. I like his Letterboxd lists (i.e. "Movies for Adults: Studio Auteur Oddities, 2004-2018" and "Aughts Eurotrash Special Effects Spectacle Cinema"), and he wrote a ton of good shit this year. My two faves of his were his piece for Pitchfork about Phantom of the Paradise and his piece for Waypoint on the DJing video game Fuser.

One of the few times I've braved the outside this year was to check out the new Uniqlo store downtown, and I might have found the greatest T-shirt ever made.

San Francisco noise-pop institution Deerhoof put out two great records this year: the post-apocalyptic Future Teenage Cave Artists and the kaleidoscopic covers album Love-Lore.

For Vanity Fair, David Kushner on prog legend Rick Wakeman.

Getting the 'rona buzz (aka #3 all over) four months after it was cool.

Good Italian toothpaste.

For Current Affairs, Lyta Gold on the fake nerd boys of Silicon Valley.

Punisher, the newest album by Phoebe Bridgers. A good chunk of my favourite lyrics and song details of 2020 are on this.

Getting a smaller desk and a better chair for my tiny computer nook.

"The Docked Yacht: AOR Cinema 1979-85."

Kayla Czaga's wonderful poetry collection For Your Safety Please Hold On.

The continuing excellence of Blank Check with Griffin and David.

The great Magic YouTube channel Rhystic Studies put out "1995: The Season of the Witch," a great video contextualizing early Magic's depiction of witchcraft within the Satanic Panic hangover.

Speaking of Magic stuff on YouTube: my brothers in playing with crappy cards on purpose, Quest for the Janklord, the pride of Roseville, Minnesota.

RTJ4, another fireball of a record courtesy of the the formidable indie-rap tag team Run the Jewels.

Chef Sohla El-Waylly rising like a phoenix from the ashes of the Bon Appétit fiasco to land a plum gig with the Babish Culinary Universe.

Related: the great Claire Saffitz starting her own YouTube channel and dropping her cookbook Dessert Person.

For the New York Times, Dave Itzkoff on Martin Scorsese.

Repurposing a big birdcage for my rats.

During my vacation towards the end of the year, I defaulted into a lounging uniform: black t-shirt, black running tights, black hoodie, black slippers. Not gonna lie, it kind of rules.

Taking pictures of neighbourhood cats.

Finally springing for a copy of the gorgeous movie-nerd card game Cinephile.

Virtual board game night with my pal Adam.

City Girl's continued run as the nea plus ultra of chill lo-fi beats to study to, with the release of the fizzy Goddess of the Hollow and, my favourite, the delicate Siren of the Formless.

This year in chillhop: Kupla's Kingdom in Blue and Life Forms; Sleepy Fish's Beneath Your Waves and Everything Fades to Blue.

Sending out a ton of custom-made postcards to friends and family for the holidays.

Not one, not two, but three dope Mountain Goats albums this year: Songs for Pierre Chuvin, Getting Into Knives, and The Jordan Lake Sessions.

For the New York Times Magazine, Sam Anderson profiles the man, the myth, the legend, "Weird Al" Yankovic.

Two audiobooks on the creative process: Austin Kleon's Steal Like an Artist Trilogy (dude has been a source of inspiration for some years now) and Jeff Tweedy's How to Write One Song.

Speaking of Austin Kleon, I really like his newsletter. (For the record: I just out and out lifted the idea for this very list from him like five years ago).

Speaking of newsletters, another one I look forward to every week is Laura Olin's.

The great William Tyler, one of my favourite guitarists, put out two bangers this year: Music from First Cow and New Vanitas.

Some pals from Mastodon started a very funny podcast about advice columns called We'll Take This One.

One of the hosts of We'll Take This One, my pal Amelia, has a very funny funny newsletter where she talks about Lifetime Original movies at length. It's called, awesomely, Don't Threaten Me with a Good Lifetime.

I updated my 200 favourite albums list! New entries include the Blasters' rip-roaring self-titled album, Scott Gilmore's yard-sale Balearic beat missive Subtle Vertigo, and the Blue Nile's melancholic sophisti-pop masterpiece Hats.

The meta-bro comedy stylings of Chad Kroeger (not his real name) and JT Parr. Their Going Deep with Chad and JT podcast is a digressive delight, and this profile in Vice gets to the heart of their appeal.

I watched a ton of Todd in the Shadows videos, so I learned a lot of stuff about one-hit wonders and major flop records.

Secret Santa by mail.

Last and First Men, the late great Jóhann Jóhannsson's wonderful minimalistic post-apocalyptic sci-fi opus. Tilda Swinton narrates our ruins.

Someone uploaded all of Orson Welles Sketchbook, the great director's BBC series from 1955, to YouTube. I could listen to this man talk for days.

So there's this Korean YouTube channel called Yummyboy, and all they show is street food being made. That's it, that's the gimmick. It's riveting.

Starting a daily writing practice in the dying days of the year.

Getting through this Year of Pestilence in one piece.

Photo: Jorge Butehrein

Photo: Jorge Butehrein

Source:

Source:

art by

art by