A is for Accent Open Mic. If I don’t plug the scene, who will? Man, I swear I only just started co-hosting this local twice-a-month reading series, but I’ve been on the mic calling up local literary stalwarts and game first-timers for about three years now. 2026 will be Accent’s seventh year, and it promises to be our biggest yet as we settle into our cool new home on St. Hubert, just off the Blue Line. I’ll just go ahead and quote my last post: if you stick around long enough, people will figure you’ve always been there. Shout out to Devon Gallant for trusting the likes of me with the reins of this operation.

B is for Blank Check with Griffin and David. I listen to a bunch of podcasts—some would say too many podcasts—but only a hallowed few are anticipated with as much fervour as the new episode of Blank Check. Griffin Newman and David Sims are nuts for this stuff; the minutiae of box office returns, Oscars ephemera, the trajectory of Hollywood careers, the trivia of film culture. They’re also just entertaining podcasters; they’re a delight whether they pop up on film-centric shows like The Big Picture or something more comedic like Doughboys. Their show’s gimmick is they go through a filmmaker’s work one title at a time, and this year alone, they covered the Coen brothers, Amy Heckerling, and the early works of Steven Spielberg (1971-93). Their back catalogue contains further riches.

C is for Cameron Walker, best known by his nom de YouTubeur, struthless. Cam’s a real interesting dude (writer, illustrator, twelve-stepper), and his specific mix of creativity, candour, DIY spirit, and weapons-grade Aussie chill is riveting. I love the way he puts videos together; they’ve always had a strong handmade feel to them, but over the last year or so, they’ve gotten more psychedelic and collage-like, with lots of Adam Curtis-y repurposed footage. Also I completely jacked the idea for this blog post from his most recent video; sorry, mate.

D is for dream pop. At one point during the fall, I told a friend of mine that I wanted to write poems that elicited the same feeling in people that dream pop elicits in me; swirly, romantic, gauzy. I listened to a shitload of Slowdive this year and concluded that my quest was a noble one. I discovered that dream pop shook hands with shoegaze a lot. I listened to Airiel’s Molten Young Lovers and concluded that there was nothing on there as good as “In Your Room,” but “Sharron Apple” comes pretty close. I learned that there was a band out there who nailed the assignment when they named themselves LSD and the Search for God.

E is for Emma Harner. This was my flukiest discovery of the year. Harner, a young singer/songwriter from Nebraska, was a guest on Matt Sweeney’s Guitar Moves, where she broke down the beating, bloody Midwest emo heart of her specific set of, well, guitar moves. Here we have a musician who shreds like a math rocker and sings like Neko Case. She only has one EP to her name, but if anything of what I just said appeals to you, get on the bandwagon and buy all the stock you can. Play “Do It” and “Yes Man” until you make converts.

F is for Fool Time. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of Jon Bois’s work, from his sprawling speculative sci-fi hyperfiction to his long-form documentary work on the history of snake-bitten sports franchises to his extended comic excursions into late-capitalist absurdity. His latest opus is typically Boisian in its mix of scope and silliness, telling the story of the people responsible for installing the first transatlantic telegraph wire through the lens of the thoroughly unmissed ‘90s sitcom Home Improvement, casting 19th-century scientists and titans of industry as either Tims (stubborn, boorish) or Als (capable, knowledgeable). The story would be engrossing without this admittedly strange throughline, but part of Bois’s project is demonstrating that history is made up of similarly strange echoes. The “Storm” segment from Part 3 is one of Bois’s best setpieces.

G is for Geese. In which rock and roll saves itself. So yes, I thought Getting Killed kicked major ass, shocker. But it’s been really fun and invigorating to watch this band meet the moment with an album that starts the way it does, with a singer who sings the way Cameron Winter sings, with their entire future in front of them. “Taxes” is as immortal as first singles get. I think these 11 songs can change you. Then again, my brain is broken a specific way where an Instagram Reel of Snoopy skating on a pond in slow motion set to “Au Pays du Cocaine” made me tear up, so what do I know?

H is for Hundreds of Beavers. This was the first movie I watched in 2025, the first Blu-ray I bought in 2025, and a legit grassroots cult phenomenon. This is a 2022 silent slapstick comedy about a fur trapper built on a foundation of Looney Tunes gags and video-game logic. The titular beavers are played by people in mascot suits. Lead actor Ryland Brickson Cole Tews looks exactly like the kind of guy you would cast in a parody of macho survivalist fare like The Revenant and The Edge, but with great comic timing. It’s just about the funniest thing I saw this year.

I is for Inoreader. I know why the real heads follow this blog: for the RSS reader app recommendations. At some point this year, my prior RSS reader spewed a bunch of surveillance state A.I. vomit all over itself, and I was in the market for something new. Inoreader came highly recommended, and I’ve been happy with it since. If Google had a lick of sense, it’d bring back Google Reader, which I still miss to this day. Here’s a sub-recommendation: filling an RSS reader full of blogs and websites you love to read will make the internet more bearable, I promise. And I’m just some dumbass; Cory Doctorow, the namer and shamer of enshittification, is way smarter than me, and he agrees.

J is for Jesse Lonergan. This is the second-flukiest discovery for me this year. The cover of Lonergan’s 2020 post-apocalyptic graphic novel Hedra stopped me dead in my tracks when I first saw it in a book store nearby. The isometric type of the title. The schematic symmetry. The head-film sci-fi trappings. The total absence of dialogue. Beautiful, abstracted visual storytelling, yes please. It scratched the part of my brain that loves Moebius, Heavy Metal magazine, and all those album covers Roger Dean drew. I want to sink my teeth into last year’s Drome as soon as I am able.

K is for Kleon, Austin. This dude just loves making shit and sharing shit, and it’s always interesting. I came across his work, specifically the totemic Steal Like an Artist, ages ago, but at this point, he’s just a cool guy with good taste and good ideas who lives with his wife and kids in Texas. Part four of his Steal Like an Artist trilogy, Don’t Call It Art, comes out in June, and I can’t wait to tear through it. I have jacked so many ideas from the man I owe him at least a beer and a sandwich at a restaurant of his choosing.

L is for letters. Inspired by the great Rachel Syme and her fantastic book on the subject, I decided to commit to writing a bunch of letters to friends, family, and in one case, a total stranger who has become a penpal. I type these letters up with my glittery burnt-orange Underwood 310 I paid for with Scrabble winnings, using fancy, fuzzy paper Steph bought me for my birthday. Nothing beats getting a letter in the mail from someone you care about. The only issue is that now I have a months-long backlog of replies to send out. This is a problem worth having.

M is for Men I Trust. It’s also for Montréal, where the band is based, and where I live. I fucking love this band. They’re my favourite local band. This year, they’ve spoiled me rotten by releasing not one, but two great albums’ worth of smooth, sophisticated indie pop. I could listen to Emma Proulx sing the STM map. Jessy Caron is kind of a hot-shit guitar player (the solo on “Seven” is the best yacht-rock guitar solo of the century). I need to ask Dragos Chiriac about his favourite synth patches. One more banger and they’ll join the Five Album Club.

N is for newsletters. Newsletters: they’re like blog posts, but for your inbox! Or your RSS feed (see the entry for the letter I) as the case may be. Here’s a bunch of newsletters I like. The Reveal, written by Keith Phipps and Scott Tobias, formerly of The Dissolve and The A.V. Club. The aforementioned Austin Kleon. The also aforementioned Blank Check’s Check Book. Channel 6, from 50% of the Shutdown Fullcast. Read Max. The hatingest haters on the island, the funny and incisive Discordia Review. Walt Hickey’s legendary Numlock News. Rusty Foster’s just as legendary Today in Tabs. Luke O’Neil’s Welcome to Hell World features great writing from Mr. O’Neil and a strong rotating supporting cast. The SPIN Magazine methadone of Anthony Cougar Miccio. Kyle Chayka’s One Thing. For the gym rats and aspirant gym rats: Casey Johnston’s She’s a Beast.

O is for One Battle After Another. Paul Thomas Anderson, one of the best to ever do it, brings us a shaggy $150 million action comedy about a stoner doofus who has to shake off the haze of weed smoke long enough to call upon his training (i.e. his past as a member of a militant revolutionary cell) to save his daughter from the clutches of a sentient fascist pec muscle. Also basically everyone involved is more qualified than him, including his kid; hilarity ensues. There’s a chase scene in this that gave me the same feeling as taking a hill too fast in a small car (complimentary). It is wild that this movie exists.

P is for The Pit: A Plateau Periodical. Chloe and Mariana saw it fit to publish a review of cinematic cyberpunk classic Burst City and a handful of poems across a couple of their issues this year. A bunch of my friends (and other cool and interesting people who are not my friends yet) can be found in their archives. Yeah, this is extremely local, but hey, I’m a citizen of my city, and sometimes things I like don’t really leave the island (although I did send a commemorative Pit matchbook to my Swedish penpal; could this be the first toppled domino that leads to a big European break?). If you want a piece of The Pit, you’ve got to come here.

Q is for quitting. It may surprise you to know that I had to stretch to find something for the Q slot. So I’ll say this: early January is the time for resolutions to oneself to get smarter, stronger, “better,” what have you. I’m going to offer a little bit of counter-programming here. That thing you’ve been doing regularly that is nominally good for you but makes you fucking miserable? Just quit. You’re under no obligation to do a damn thing. There’s no dishonour in quitting something that sucks ass or is boring or just isn’t worth the squeeze. You get one shot at this, and you’re better off spending it doing something that nurtures enthusiasm. This is your permission slip.

R is for The Rewatchables. This is the “dudes rock” entry. If you’re the kind of person who says “man, they sure don’t make ‘em like they used to” after watching a perfectly competent studio drama for adults from 1997, you’ll get a kick out of this show. Bill Simmons isn’t exactly Ben Mankiewicz (nor does he profess to be), but he surrounds himself with a strong supporting cast of Ringer regulars (Sean Fennessey! Chris Ryan!) and special guests (Cameron Crowe was just on to talk about Hal Ashby’s Shampoo) for avuncular bull sessions covering the cable canon.

S is for Sinners. The most fun I had at the movies all year. An imaginative, sexy, crowd-pleasing genre blockbuster with awesome music, a half-dozen or so great performances, and strong thematic depth (man, vampires truly are the Swiss Army knife of metaphors; religion, cultural appropriation, conformity, sexual mores, etc). Ryan Coogler has many gifts as a filmmaker but his most unheralded strength is imbuing his films with a strong sense of place; you can practically smell the liquor wafting off the screen.

T is for Teenage Engineering. This one’s kind of aspirational: I’ve been thinking about acquiring some noisemakers to join my beat-up acoustic guitar and my Stylophone and the free DAW I downloaded last week (I will only admit to the amount of time I spent trying to replicate Mark Sandman’s bass tone in Cakewalk under threat of grievous bodily harm). These Swedes make sleek synths and samplers and assorted audio equipment, but for our purposes, they make the Pocket Operator series. That PO-33 looks fun as hell to mess with. I’ve seen people do crazy things with these machines on YouTube.

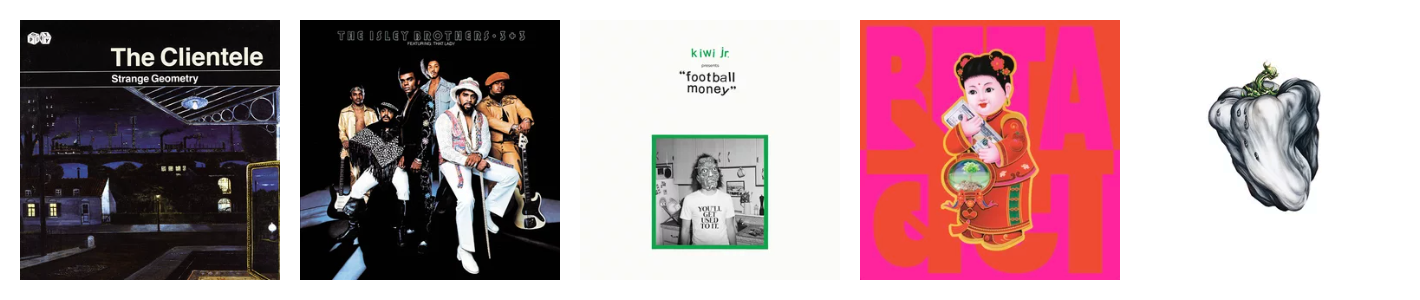

U is for Used book/record stores. A PSA: if you’re thinking of giving away your collection of records or CDs or tapes or DVDs or Blu-rays in the name of minimalism, don’t. You will regret it. Ask me how I know. Anyways, I spent most of 2025 buying physical media, because a CD pressing from 1993 will still play on my thrifted stereo during the nastiest Cloudflare outing, and I don’t have to polish Daniel Ek’s boots with my tongue for the privilege of listening to it. Shout out to Cheap Thrills. Shout out to Encore Books and Records. Shout out to Librairie Phoenix. Shout out to l’Échange. Shout out to the Word. Shout out to Aux 33 Tours. Shout out to that shop in front of the entrance of the BAnQ. Hell, shout out to the Value Villages in the suburbs.

V is for Les Voyeurs de vues. If I were feeling reductive, I would call this the Queb Blank Check. But Yannick Belzil and Alex Rose transcend that description with a format that’s more freewheeling (each host runs down their week in movie watching before comparing notes on two “movies of the week”) and a lived-in, intimate atmosphere; they frequently record at a bar, their banter soundtracked by whatever’s playing over the PA that night. Sometimes they get interrupted by curious patrons. The whole enterprise feels like eavesdropping on a great post-screening conversation. Call it podcast vérité.

W is for Wilco, who narrowly won the title of “band I chainsmoked to the filter the most in 2025” away from another W band, Ween. It wasn’t just the music I chainsmoked; it was Jeff Tweedy’s three books, Jeff Tweedy’s triple album from this year, live bootlegs on YouTube, podcast interviews, niche Instagram accounts, just a lot of ancillary material in addition to the mainline stuff. Steph even bought my a remastered version of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot for Christmas. Speaking of Christmas…

X is for Xmas. Another stretch, I know. Bear with me, we’re almost done. Every Christmas, I feel a little bad for how spoiled I am. My sister got me a sweet pair of Grado headphones. My mom got me a Polaroid Flip. In addition to the copy of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Steph got me a snazzy mechanical keyboard that’s modelled after the Nintendo Famicom; it comes with these two chunky buttons that you can program macros to; I made it so they type em-dashes and en-dashes.

Y is for Yacht Rock, not so much the genre but the ongoing projects of the creators of the 2005 web series. 2025 saw the welcome return of Beyond Yacht Rock (now Beyond Yacht Rock 2000), a celebration of arbitrary genres of the host’s devisal (recent examples include Glum [glam rock bummers] and Hobbit Metal [metal about Hobbits]), and the continuing saga of The Yacht or Nyacht Podcast, a comedic quixotic quest to catalogue and taxonomize the various West Coast sounds of the 1970s and 1980s. RIP Billion Dollar Record Club, a format I actually quite liked.

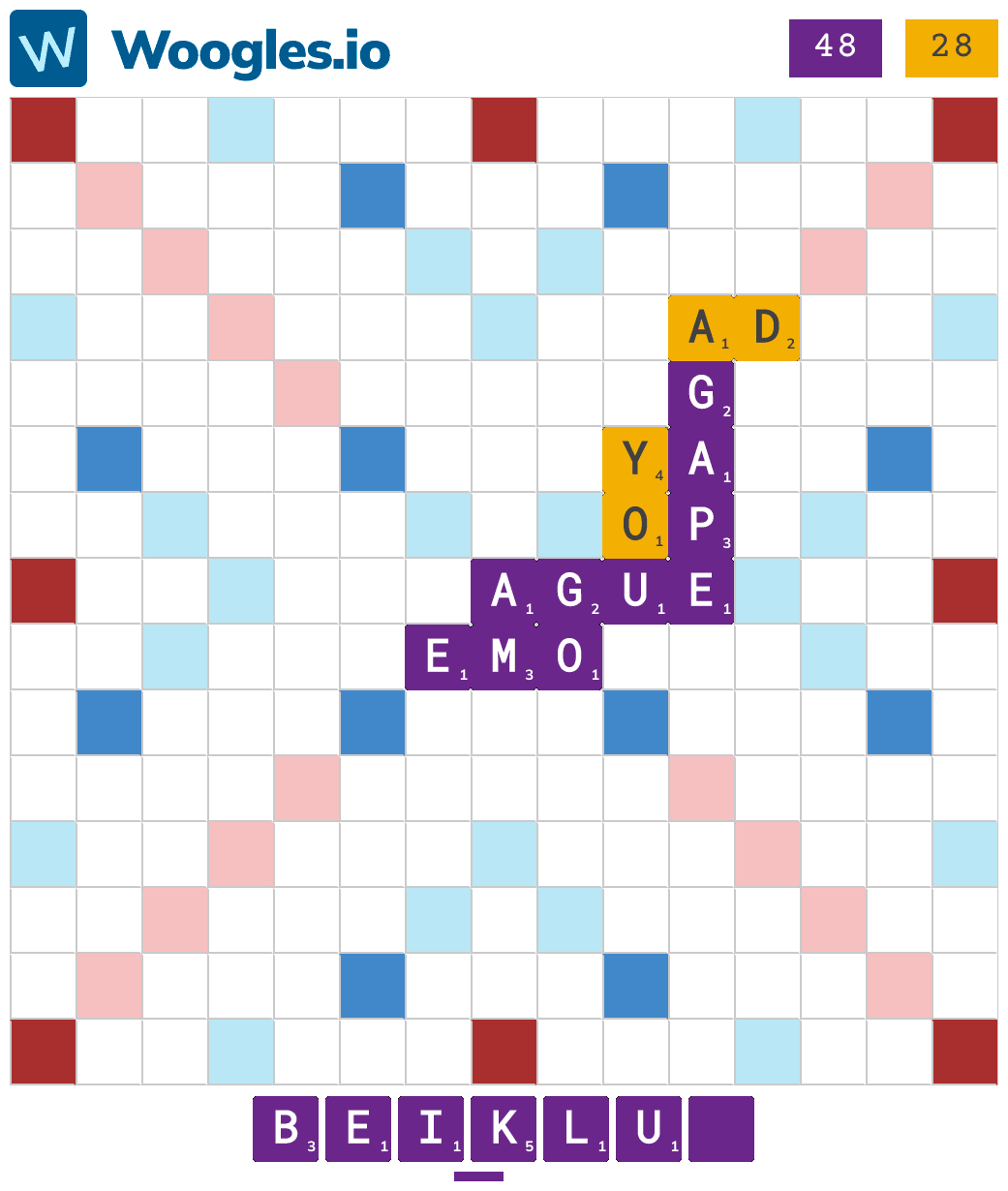

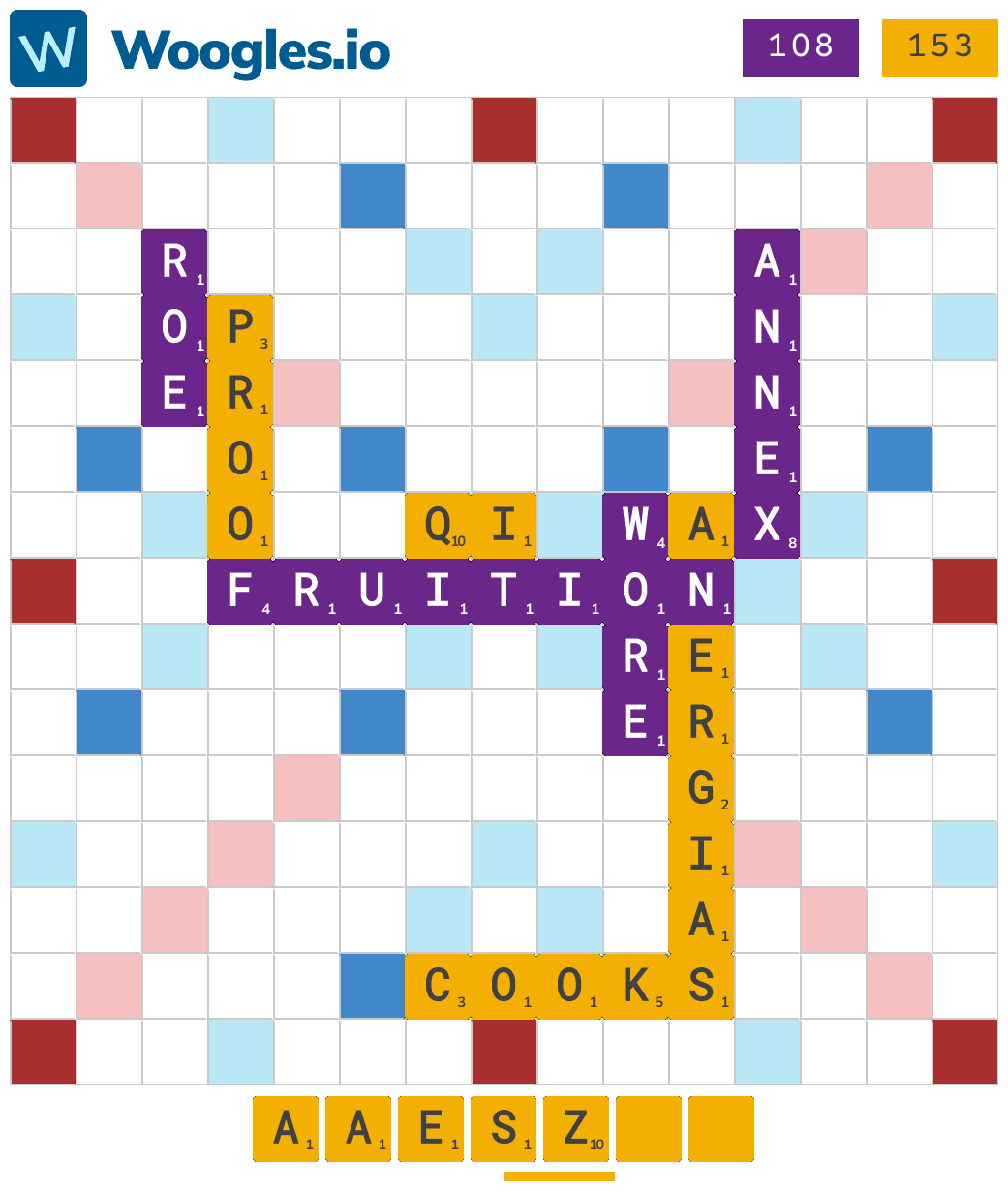

Z is for Zyzzyva. This is the Scrabble entry on the list; Zyzzyva is the industry-standard study tool for pros and noobs alike. 2025 was my second full year of tournament play. I played in 11 tournaments, won one, and gained three whole rating points (my 4-11 crashout in Belleville in February really did a number on my rating). But I’m on the doorstep of quadruple digits, I’m still being coached by a national champion, and with any luck, I’ll be rated as a strong intermediate by this time next year.

Here's to 2026!